The Five Personalities of Innovators: Which One Are You? March 23, 2012

Posted by Marta Karolak in Uncategorized.4 comments

Two days ago Forbes ran an article with the above title. The piece touched upon many of the topics that we discussed with Carl Bass during our visit to Autodesk earlier this week. Here are a couple of ideas and quotes I wanted to highlight:

A company needs a balance of innovators and “non-innovators” to thrive

The Forbes study (upon which the article is based)…..”isolates and identifies five major personalities crucial to fostering a healthy atmosphere of innovation within an organization. Some are more entrepreneurial, and some more process-oriented – but all play a critical role in the process. To wit: thinkers need doers to get things done, and idealists need number crunchers to tether them to reality.Though it may seem stymieing at times, in any healthy working environment, a tension between the risk-takers and the risk-averse must exist; otherwise, an organization tilts too far to one extreme or the other and either careens all over the place or moves nowhere at all. An effective and productive culture of innovation is like a good minestrone soup: it needs to have the right mix and balance of all the ingredients, otherwise it’s completely unsuccessful, unbalanced — and downright mushy.”

Corporate culture definitely impacts innovation

…..”the corporate environment – is a stealth factor that can make or break the potential of even the most innovative individual. Look at it this way: a blue whale is the largest animal known ever to have existed, but if you tried to put it in a freshwater lake, it wouldn’t survive. Well, that and it would displace a lot of water. My point? Even the largest and mightiest of creatures can’t thrive in an environment that doesn’t nurture them.”

Here’s the link to the full article (so that you can check out which one of the five personality types you are!): http://www.forbes.com/sites/brennasniderman/2012/03/21/the-five-personalities-of-innovators-which-one-are-you/

Experience Design (2001 Edition) – Nathan Shedroff March 20, 2012

Posted by Marta Karolak in Uncategorized.4 comments

Summary

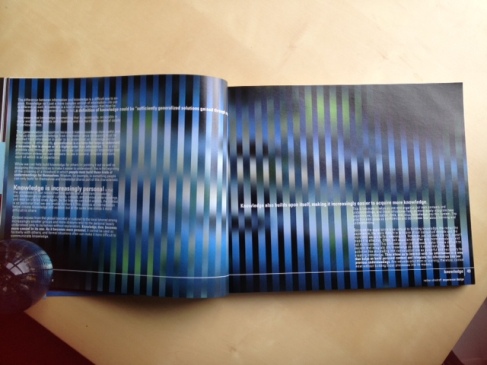

At its core, Experience Design by Nathan Shedroff is about conveying the power of experience and illuminating to readers how understanding that can be leveraged in design. The author’s ingoing premise is that everything = experience. To that end the layout of the book itself is intended to demonstrate the concept. – The book’s only table of contents is presented non-sequentially on the front cover, and chapter demarcations are obscured. – Within the pages of the book the author demonstrates his point further on two levels: 1) by an array of visuals and typography convened on the pages, and 2) by offering countless experience examples (almost 1 on each page of the book) ranging from his visit to the Institute de Monde Arabe in Paris to the NASA J-Track website to a close-up of the 1040EZ tax form. He uses each example to highlight various concepts relevant to design. The range of topics is broad, including such things as product taxonomies, taste, user behavior, subjectivity, and cognitive models. To a large extent, the examples are left to speak for themselves without explicit explanations for their inclusion. Thus, each reader is invited to contemplate and digest individually, partaking in the experience design experiment that is the book. To view several images of page layouts from the book, please visit www.experiencedesignbooks.com.

Critical analysis

The concepts Shedroff presents, while rooted in his background and particular segments of the design world, seem relevant for all design disciplines and actually to life and human interaction overall. There were two that I found particularly engaging.

The first is the distinction and relationship Shedroff draws between data, information, knowledge, and wisdom. One moves along the chain by adding context and understanding.

Shedroff is critical of the data overload in our society. However, he also states that as we move along this spectrum we move from more generalized to more personal contexts: “Wisdom is so personal that it cannot be shared with people.” That begs the question of how we are supposed to share meaning and not just data or information? Won’t we necessarily be presenting our very subjective perspectives and interpretations the further right we try to move along that chain? What is the optimal point and method for allowing people to formulate their own opinions? Storytelling & conversation are held up as models for creating context for individuals and allowing them to connect to data and information. I understand and appreciate the power of these tools, but also immediately think of modern day television “news” programs, whether liberal or conservative, and the amount of story telling and opinion that is currently offered as “facts”. In the end, though, it seems that truth can be obscured by false data or false stories so it is better to place data in context and relay things in ways that are more approachable and digestable as Shedroff proposes.

The second concept that particularly caught my attention is experiential learning, which the author regards as the best way to convey knowledge. I agree and couldn’t help but think of the changes to the Haas curriculum in the last two years that embrace that perspective. All MBA students are now required to take Problem Finding/Problem Solving (which introduces students to concepts and methodologies of Design Thinking) and at least one experiential learning course (e.g. Entrepreneurship, Haas@Work). I also couldn’t help but think of the various theories and approaches to primary education in the U.S. that I have researched for personal reasons over the last year. Only one, Waldorf, seems to have its foundation in experiential learning. Disciplines such as handwork (woodworking, sewing) and eurythmy (a movement art) are part of the core curriculum for children in grades 1-8. Interestingly, Waldorf education simultaneously eschews much of today’s technology for this same age group, in part because of the data overload that it introduces into children’s lives. An October 2011 NY Times article discussed why many of today’s top tech leaders in the Silicon Valley are choosing Waldorf education for their own children: http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/23/technology/at-waldorf-school-in-silicon-valley-technology-can-wait.html?pagewanted=all

I would be curious to hear Shedroff’s thoughts on the intersection of education and technology, which is obviously central to his career and many of the perspectives presented in the book.

My appreciation for the concepts Shedroff chose to highlight is offset by the design of the book itself. On one hand the layout is thought provoking. On the other hand, that same layout and more specifically the design of individual pages, seems to precisely miss on the author’s key point regarding experience design: “Experience design is the deliberate, careful creation of a total experience for an audience.”

While the layout makes the book very accessible – it is easy to flip to any given page for a free-standing example or takeaway on design – it is not conducive to painting a coherent story or drawing the reader into a narrative. One can equally easily set the book down after flipping through several pages. This is especially true since many examples seem disjointed – profound reflections on the constancy of human birth and death are followed abruptly by a page featuring match.com. Perhaps these examples could be better leveraged if the author integrated them somewhat with one another or linked them more directly to the core concept of their “chapter” (whose theme is completely unapparent when one is on either of those given pages)?

The downside of the layout is exacerbated by the poor aesthetic of many individual pages. There is simply too much small text everywhere. Ironically, there is data and sensory overload – the presentation is not simple or clean (akin to bad PPT presentations), challenging some basis fundamental concepts of “good design.”

It is hard to absorb messages when they are presented in such a way and I am perplexed by the author’s choice to communicate this way. What should we make of these types of pages?

Are they intended as examples of what NOT to do? Of how bad design can completely miss delivery of its message because many readers may simply disengage from the experience and flip past such “messy” pages?

What is the value & relevance of this book?

The book uses examples from the time of its creation to illuminate broader concepts that could be applied to any design process, at any time. The specific examples, however, make it very much a book of its time. When it was published in 2001, it must have been very much at the cutting edge of an intersection of various design disciplines (interaction design, information design) and the internet explosion. Much of the discussion in the book and the examples used focus around websites or tech devices prevalent at the time (e.g. Blackberry). Reading the book today almost feels like a visit to an information design/internet museum of the late 1990s. It is fun, but raises the question whether the book is still useful 11 years later or whether it is now dated. (That is likely the reason the book was re-published with new examples in 2009). It is also hard to overlook the difficulties the layout of the book poses since its design is so intricately intertwined with the topic the book presents.

I would recommend the book to anyone looking for a coffee-table addition of “soundbites” for reflection on design. As stated previously, one doesn’t have to read the book sequentially. Flipping to any given page will do. I would not, however, recommend the book to anyone looking for an introduction or comprehensive discussion of concepts and methodologies relevant to the design field. It is too confusing and busy to serve that purpose.

If you do choose to read the book, I offer the following user experience assessment diagram from Peter Morville of Semantic Studios for evaluating the book: