Sketching User Experiences by Bill Buxton March 14, 2011

Posted by karimcglynn in Sketching User Experiences.trackback

Sketching User Experiences by Bill Buxton is a vast collection of historical lessons, examples of best practices, and real world case studies from the world of industrial/interaction/experience design. It is a testament to the power of design as a competitive strategy, a practical field guide for applying good design processes, and an argument for the power of sketching and experiencing ideas rather than simply thinking and talking about them.

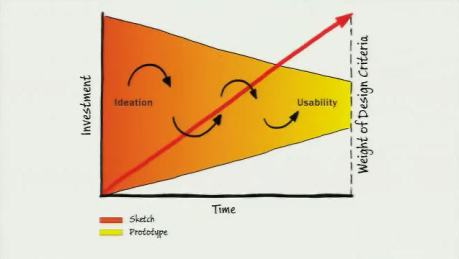

Buxton’s idea of “sketching” is broader than the traditional concept of a rough drawing. Rather, Buxton defines sketching along a continuum which he calls the “design funnel”, which starts with rough drawings (ideation stage) and increases in fidelity to the point of prototype (usability stage). Along that continuum Buxton illustrates many examples of “sketches”, including various types of drawings, 3D sculptures, storyboards, stop-motion animations, and video demos, among others.

The central point of Buxton’s book is that there is a different level of sketch-fidelity appropriate to each stage in the design process and what you need to convey at that time. Countering the assumption that if you are going to create a depiction of an idea you will want to make it as concrete as possible, Buxton argues that making certain features of the design too visually concrete at the wrong stage can mislead team members and prematurely cut off further ideation for that feature.

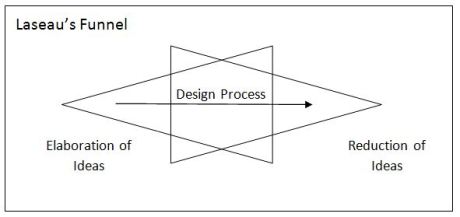

Buxton’s main thesis is consistent with the increasingly popular mantra of “fail early and fail often” as a guiding strategy for any creative endeavor. The value of his sketching methodology is in producing many low-cost sketches up front, then gradually decreasing the number of options while increasing the fidelity of each subsequent sketch. As he points out, this methodology is consistent with Laseau’s Funnel (1980), a description of the design process as the overlap between “Elaboration” (a process for opportunity-seeking) and “Reduction” (a process for decision-making).

While some might find Buxton’s description of the idealized design process to be the obvious approach in a perfect world, he also provides some practical examples for how to better implement it in the real world. One of the main messages of his book is the value that a culture of sketching can bring in the form of sharing possible solutions—an important part of the ideation and decision-making processes. He provides several inspiring examples of how different design teams have developed spaces in which they can share their sketches and offer each other constructive feedback. Buxton emphasizes that it is important for designers to “live with their work” and discuss it, rather than waiting for formal crit sessions in order to share things.

Sketching User Experiences is an inspiring work for anyone who is interested in working as a designer, or anyone who is interested in the power of design thinking to transform business. However, the greatest value comes from Buxton’s encyclopedic knowledge of the biggest ideas in interaction design from the past 50 years. The bibliography of this book alone is a tremendous value to anyone who wants to imagine the future of interaction design through a better understanding of its past.

Kari – Bill does indeed, have an encyclopedic knowledge of user interaction design techniques. Perhaps another way to look at his notion of sketching is to equate it to prototyping. We often think of sketching as being about a drawing and prototyping as being about a model – these apply in the physical world, the distinction is less useful in the user interaction world.

Kari

Nice summary. Thanks.

Jon

The relationship between sketching and prototyping is an interesting onem and kind of key to what Kari was saying. I see them as two extremes of a continuum, along which one navigates while working through the design funnel. Each is characterized by the following attributes:

Sketch Prototype

Evocative Didactic

Suggest Describe

Explore Refine

Question Answer

Propose Test

Provoke Resolve

Tentative Specific

Noncommittal Depiction

What I hear Kari saying, which is key to what I write (and believe), is that we too often leap into the right column far too early in the process. My belief/hope is that by using the term “sketch” and “prototype” carefully, in terms of this continuum, that we will make better choices of when to use each.

Thanks!

Wow–thanks for your response Bill!

I completely agree that “we too often leap into the right column [of full-blown prototype] far too early in the process.” This may be a symptom of the old “waterfall” method for development, where (at its worst) design requirements are established up front and months later a fully-functional prototype emerges from the darkness.

I think your sketching methodology is a practical way to make any design team more “agile” by encouraging them to consistently refine their ideas throughout the design funnel continuum. In addition, low-fidelity sketching/prototyping tools like Balsamiq have emerged to help us create things somewhere in the middle of that continuum.

I think the greatest challenge–and I would love to hear your thoughts here–is in bringing together both agile design AND agile development in a holistic way. While each discipline has championed an “agile” approach in the past few years, I’m not sure that both processes are working together as smoothly as they could be.

Kari, Bill –

I tend to use “prototype” to describe a whole continuum from high fidelity to low fidelity – although I am fully aware that is sometimes a difficult concept for people to grasp and that they often equate “prototype” with a full-blown high fidelity prototype. The only issue I have with sketching at the left end of the spectrum is that there are ways of doing low-fi very conceptual prototypes that sometimes are more effective than a sketch – true in architecture anyway, where you are trying to understand formal and spatial relationships.

Thanks for the discussion. Good dialog.

— Jon

Jon

I think that we are getting tangled up in terminology – but not just. First, it is important to be clear that a “sketch” can be rendered in many ways, not just a drawing (which just happens to be the most common form of sketching). That is why I spend considerable time going meta, so to speak, and defining a sketch by both its attributes and – more importantly – its intent and function in the design process. Rather than low and high fidelity “sketches” or “prototpyes”, I would prefer the use of the terms “renderings” or “representations”. And, my hope is that designers think more about what is the “right” fidelity rather than high or low. And understanding when or why something is “right” is a key part of design education.

People often consider “low fidelity prototyping” as comparable to sketching. Based on the literature, I would argue that that is not the case, similarity of representations notwithstanding. It is the intent/purpose, as much as the rendering style that is important. See Snyder’s book on Paper Prototyping, for example. While the paper renderings are consistent with what is generally called “low-fidelity prototypes” and have the superficial appearance of what one might reasonably call sketching, the book has almost nothing to do with ideation or sketching, as those terms are traditionally used in the design process. It is all about how to do inexpensive usability testing – something that, as described (even with paper prototyping), is nevertheless expensive. It is something that belongs later in the design process. The appearance and materials may make you think you are sketching, but that is just not the case. That book, and most articles about “low fidelity prototyping” are about inexpensive usability testing, rather than multiples, critique, etc.

Sorry if I’m running on a bit. But I think that the point is worthy of discussion. All the best.

Hi Bill –

I see what you mean and understand the distinction you are making above and in your book. I’m still not sure “sketch” is the right word. My background is architecture and there are types when you want to make a very rough model – in fact a sketch model – that is not a drawing. I guess i get hung up on sketch as a drawing metaphor. Sketching is certainly the most commonly used early way of thinking in industrial design. Not sure as we look at an expansive set of design disciplines. In any case, I get where you are going – I’m just not sure sketch is the right word – but I do see the distinction from low-fi prototype.

BTW, In the book, I also saw what I consider a bit too much conflating of design and art. I fully agree about the need for professional design education – but think it is different from art education, although some design schools offer an MFA. By conflating design and art – I think we get people off track because art implies some level of artistic skill/craft – and that may limit some people from considering themselves designers. Of course digital tools take the whole issue of craft in a different direction.

— Jon

Ahh – but I suspect that if one does not have any kind of artistic (small “A”) skill/craft, one is probably better suited for some other profession than design. Everyone is not a designer, and not everyone is suited tempormentally or skill-wise to be one either. (But then, one could same the same about medicine, engineering or carpentry.)

Having said that, the thing that makes the statement far less dogmatic or elitist than it might seem on the surface, the nature of the “art”, “skill” or “craft” can be as (or more) diverse than the media that I would consider falling into the realm of sketching. So someone (like me) is pencil challenged, and can’d draw. That doesn’t eliminate one from becoming a designer (or artist – just look at Robert Raushenberg!). But it may well constrain what aspect of design one is suited for. I may be comppetent in interaction design, but I have no business doing graphic design, for example.

I cannot imagine design without craft. But I can imagine a wide range of crafts within design. And all of them incorporate sketching – and prototyping, I suspect. But while each may be different in medium, I suspect that all sketches have attributes in common, such as the ones that I speak of in the book:

• Quick:

• Timely:.

• Inexpensive

• Disposable

• Plentiful

• Clear vocabulary:.

• Distinct Gesture.

• Minimal Detail:

• Appropriate Degree of Refinement

• Suggest & explore rather than confirm

• Ambiguious

I respect your hesitation about the appropriateness about my use of the term sketch. Yes, it comes with baggage, some of which I conveniently (for me) choose to ignore or downplay. But likewise, almost all terms have some baggage. Hence, my sense was to make the best of what there was to work with. But that is why I try to be clear about narrowing (or broadening – depending on one’s perspective)how I use the term: sketches share the attributes in that list – a list that makes no mention of medium.

Not sure this helps, but is at least a kick at the can.

Thanks for the thoughtful reply.

Hi Jon and Bill,

Interesting dialog about ‘design’ and ‘art’! I agree with Bill that design requires a certain level of craft, and perhaps artistic skill. A designer should be able to communicate his ideas clearly through a drawing or a physical model. One who can’t communicate his ideas clearly through any medium does not truly understand his own idea. I feel that a designer – those that draw with pencils and those that make physical models – should be able to pay attention to everyday details to produce a well crafted ‘sketch’ or ‘prototype’.

I am a bioengineer, but I have taken classes with mechanical engineers and I’m always disappointed that they cannot build with Legos or draw a quick 3D sketch of objects (I guess I assumed if they can build robots with CAD, then they should be able to draw by hand too). Since most engineers are experts in using CAD software nowadays, it seems that hand drawing skills are unnecessary. I agree with Jon that digital tools have enabled many people who are ‘pencil-challenged’ to become ‘designers’.

However, I believe that being capable of forming lines freely on paper through drawing or molding a physical model with one’s hands speaks greatly to how deeply one understands a design idea.

Sophie

Mr. Buxton,

I really appreciated the Stanford video:

Now I _have_ to buy the book!

BTW: I give good pencil.

Dang, WordPress dropped the link to the video!

It’s on YouTube–you can find it if you search for “Sketching and Experience Design”.

Sketching and Experience Design: